In June 2017, the Harvard Law School Program on International Law and Armed Conflicts published a briefing on ‘Armed Non-State Actors and International Human Rights Law: An Analysis of the UN Security Council and UN General Assembly’. In this blog post, I demonstrate why the briefing – and the data collected in the annexes – is an important addition to knowledge in this area that will facilitate important discussion of this issue amongst policy makers. In order to start this discussion, I highlight a few particular aspects of the report that I find most interesting and valuable. In doing so, I explain inter alia why I disagree with the authors’ conclusion that no pattern is discernible in how the United Nations Security Council and General Assembly address armed non State actors. I end the post by giving some suggestions about how the data collected by the study may provide rich potential for even further analysis.

In June 2017, the Harvard Law School Program on International Law and Armed Conflicts published a briefing on ‘Armed Non-State Actors and International Human Rights Law: An Analysis of the UN Security Council and UN General Assembly’. In this blog post, I demonstrate why the briefing – and the data collected in the annexes – is an important addition to knowledge in this area that will facilitate important discussion of this issue amongst policy makers. In order to start this discussion, I highlight a few particular aspects of the report that I find most interesting and valuable. In doing so, I explain inter alia why I disagree with the authors’ conclusion that no pattern is discernible in how the United Nations Security Council and General Assembly address armed non State actors. I end the post by giving some suggestions about how the data collected by the study may provide rich potential for even further analysis.

Systematic review of UN practice

At its heart, the briefing addresses the important and controversial question of when armed groups have obligations under human rights law, which is the subject of my recent book The Accountability of Armed Groups under Human Rights Law (OUP, 2017). The briefing was motivated out of an observation that a classical conception of human rights law, under which States are the only duty-bearers of human rights obligations, is increasingly put under pressure, by two interrelated developments. Firstly, certain entities and scholars are increasingly recognising the possibility that non-State entities (e.g. armed groups) bear human rights obligations. Secondly, armed non State actors (ANSAs) are increasingly controlling access to territory and exercising control over civilian populations.

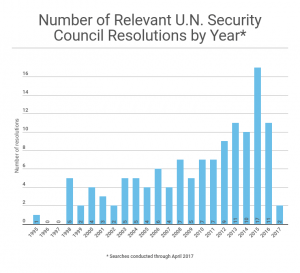

In the briefing, the authors conduct a much-needed and systematic review of the modalities in which the UN Security Council and UN General Assembly have addressed ANSAs with respect to human rights law. In doing so, they identify and review over 125 UN Security Council resolutions, approximately 65 UN General Assembly resolutions and over 50 UN Security Council Presidential Statements. The study not only takes note of the language employed, but also analyses the geographical, temporal and material scope of the implied accountability. It concludes by discussing the consequences of these organs establishing the responsibility of ANSAs in relation to the protection and fulfilment – or at least, the non abuse – of human rights.

As someone who has devoted significant time to the analysis of the accountability of armed groups under human rights law in recent years, I am particularly pleased to see that the practice of the Security Council and General Assembly on this issue has now been collected, because little systematic analysis of this issue has ever been conducted (see Constantinides for an earlier review of SC practice in this regard). During the course of my own research on the topic, I maintained a rough tally of UN practices but the compilation of a complete collection of relevant UN practice was not one of my research aims. However, at many times during my research on this issue, I thought that such a collection would be helpful as it might assist inter alia to clarify States’ views on the matter.

1995-2017: UN practice

Indeed, the findings of the study are very elucidating, as they shed light on the UN’s practice on this matter from 1995-2017. For example, it is particularly interesting to see how starkly practice on the matter has increased since 2000 and the graphics convey this information effectively.

The analysis of the material scope of the UN documents is also valuable as it clearly demonstrates the types of violation that the Security Council is addressing and the language in which they are condemned. It is also interesting, for example, to see that the Security Council at times calls upon ANSAs to ‘prevent’ human rights abuses or ‘protect’ human rights, in addition to requesting them to ‘respect’ human rights. The report also highlights instances of particularly noteworthy or unusual language, that might shed light on the scope of human rights obligations to which armed groups are being held. For example, the report highlights an instance in which the Security Council urges the RCD-Goma, as the de facto authority, to protect the “rule of law” in the region under its control. The report also notes the instances in which the human rights obligations of armed groups, have been invoked alongside those of States. The report also helpfully notes which Security Council resolutions were issued under a Chapter VII mandate.

The analysis of the material scope of the UN documents is also valuable as it clearly demonstrates the types of violation that the Security Council is addressing and the language in which they are condemned. It is also interesting, for example, to see that the Security Council at times calls upon ANSAs to ‘prevent’ human rights abuses or ‘protect’ human rights, in addition to requesting them to ‘respect’ human rights. The report also highlights instances of particularly noteworthy or unusual language, that might shed light on the scope of human rights obligations to which armed groups are being held. For example, the report highlights an instance in which the Security Council urges the RCD-Goma, as the de facto authority, to protect the “rule of law” in the region under its control. The report also notes the instances in which the human rights obligations of armed groups, have been invoked alongside those of States. The report also helpfully notes which Security Council resolutions were issued under a Chapter VII mandate.

Patterns: Now you see them, now you don’t….

When reviewing the report’s findings, I was surprised by the authors’ conclusion that “no clear pattern or practice emerges” from the Security Council or General Assembly with respect to the use of the terms ‘abuses’ or ‘violations’, because my own analysis has indicated that recent resolutions demonstrate a consistent approach to this issue, albeit slightly coded. Indeed, as I mention in my book, since 2013, I have noted a clear trend for the Security Council to:

- always refer to infringements of international humanitarian law as ‘violations’ (NB: never ‘abuses’), irrespective of whether it is addressing a State or armed group;

- refer to infringements of international human rights law by States as ‘violations’; and

- refer to infringements of international human rights law by armed non State actors as abuses.

Employing this approach, it can be seen why Security Council resolutions since 2013, that address both parties to a non-international armed conflict involving a State and armed non State actor, express serious concern about “violations and abuses of human rights law” (see S/RES/2265. S/RES/2293, S/RES/2295, S/RES/2299, S/RES/2340, S/RES/2327). In my view, the juxtaposition of the terms ‘violations and abuses’ in such resolutions does not demonstrate ambivalence to the terms’ differences or a view that they are synonymous. Instead, in my view, the Security Council is using a shorthand. The use of the first term “violations” refers to the supposed infringements by the State and use of the second term “abuses” refers to the supposed infringements by the armed group. In a similar vein, when a Security Council resolution addresses only an ANSA, it talks about the “violations of international humanitarian law and abuses of human rights law” (see S/RES/2293, S/RES/2277, S/RES/2331, S/RES/2349). As far as I can see, one has to go back as far as somewhere in 2013 to find a country-specific variation on this formulation. Moreover, an identical pattern can be discerned in the General Assembly Resolutions and UN Security Council Presidential Statements that have emerged since 2013.

While it might be tempting to argue that this emerging practice evidences a view that States are bound by human rights law and armed groups are not, actually the same resolutions and statements (distinguishing ‘violations’ from ‘abuses’) almost always contain exhortations to both parties to adhere to their ‘obligations’ under both bodies of law.

Abuses/ violations: possible explanations?

It is also interesting to note the explanation that the authors of the report put forward as a possible explanation for the different uses of the term ‘abuses’ and ‘violations’. Indeed, the authors suggest that the use of the two terms may be explained by differences between the obligations to ‘respect’, ‘protect’ and ‘fulfil’ human rights. In doing so, the authors assert that the UN Security Council might use the term ‘abuse’ to describe conduct of ANSAs which fails to respect human rights and the term ‘violation’ to describe the conduct of ANSAs that which fails to protect or fulfil human rights. While this is an interesting proposition, it is unusual because it implicitly suggests that the Security Council might be more willing to find ANSAs bound by an obligation to ‘protect’ or ‘fulfil’ human rights (justifying the word ‘violation’) than by an obligation to ‘respect’ human rights (explaining the word ‘abuse’).

Notably, in recent studies on the topic of armed groups and human rights law, the reverse position has been taken (see Daragh p. 276, Fortin, 391), on the basis that generally obligations to protect and fulfil human rights require greater capacity on the part of the ANSA, than obligations to respect, and often their fulfilment constitutes a greater challenge to a State’s sovereignty. The explanation proposed by the report also does not taken into account the fact that human rights treaty bodies have long recognised that a State’s failure to respect, protect or fulfil human rights equally give rise to ‘violations’. In my view, the variations in practice prior to 2013 can be better explained by the drafters of the resolutions (i) not giving enough attention to the issue in early reports and (ii) being uncertain regarding the legal legitimacy of holding armed groups to account under human rights law.

Conclusions

In addition to provoking valuable discussion on these and other points, the report and the underlying database contained in its annexes will be an important tool for scholars, policy-makers and States who are interested in this issue. Indeed, the data collected by the study provides a rich potential for even further analysis. For example, when analysing the various documents from a temporal and geographical perspective the study is largely concerned to understand which countries have been under review, in which year. It could also be interesting to analyse the documents, to discern:

- the moment in the armed conflict time-line that the human rights terminology is employed i.e. before, during or after the threshold of international humanitarian law had been met? This issue is somewhat analysed at p. 14 of the report, but I think a more systematic analysis of this issue would be interesting.

- the level of territorial control the armed group in question has – if any – at the time it was addressed by the UN body?

Analysis on these questions would shed even more light on views about the factual conditions in which armed groups may be considered to have human rights obligations and whether (and how) these conditions may correspond to the threshold of international humanitarian law and control of territory. It would also of course be fascinating if further empirical research was conducted on States’ views of this issue.

Katharine Fortin’s book the Accountability of Armed Groups under Human Rights Law was published on 10th August 2017 with a foreword by Professor Andrew Clapham.